I paint for the same reasons I write: it’s a physical activity that is peaceful, happy, and all about light. Though for some time now I’ve not been painting much. When I do paint, the images come from some underground reservoir, the same place many poems come from, a vision from the inside, if I can say so without sounding too psycho, as opposed to en plein air, painting what one sees on the outside. I read recently that Monet painted dozens of scenes of the River Seine – the same scene over and over, but each scene in different light. I’ve never seen a Monet painting in person, only pics of them, often the light different in each photo, and I’ve often wondered what Monet would think of that, the light in his paintings changing with each reproduction. The light in a parlour or museum likewise might change the scene as it was seen and painted. That effect is not unlike sound effects, where the splendid, carefully practiced arpeggio heard on the radio is accompanied by static, a dog barking in some distant yard, or a trash truck picking up the street cans and noisily dumping them into the void.

I did see some Rothko paintings in person, some time ago, at a show at the Portland Art Museum, and I was surprised by how thinly he applied the paint to the canvas. You could easily see the warp and weft of the canvas. Of course you’re supposed to view from a distance – the same distance for everyone? One’s eyesight too changes the light. Way back in my school days, I once tried to argue that Monet’s impressionist style was the result of cataracts, but I was struck down by an art student who argued that the work of the impressionists was the result of an art theory they had invented and implemented as a complicated statement on reality and vision. I still think it might have been cataracts.

I started painting with my two granddaughters when they were little and liked to play with paints, unconcerned with talent or any kind of “I can’t draw” self-criticism. We all three painted for the same reasons mentioned above: peaceful, happy, and light. And fun! At first I bought new canvases from an art supply store, of modest size, 20″ by 20″ or so, but I then started to find large canvases at garage sales, priced cheaply enough, far less than I was paying for the new ones at the art store, and I bought them for us to paint over. The garage sale finds were not Monet’s or Rothko’s, so no harm was brought to the art world by our painting over them.

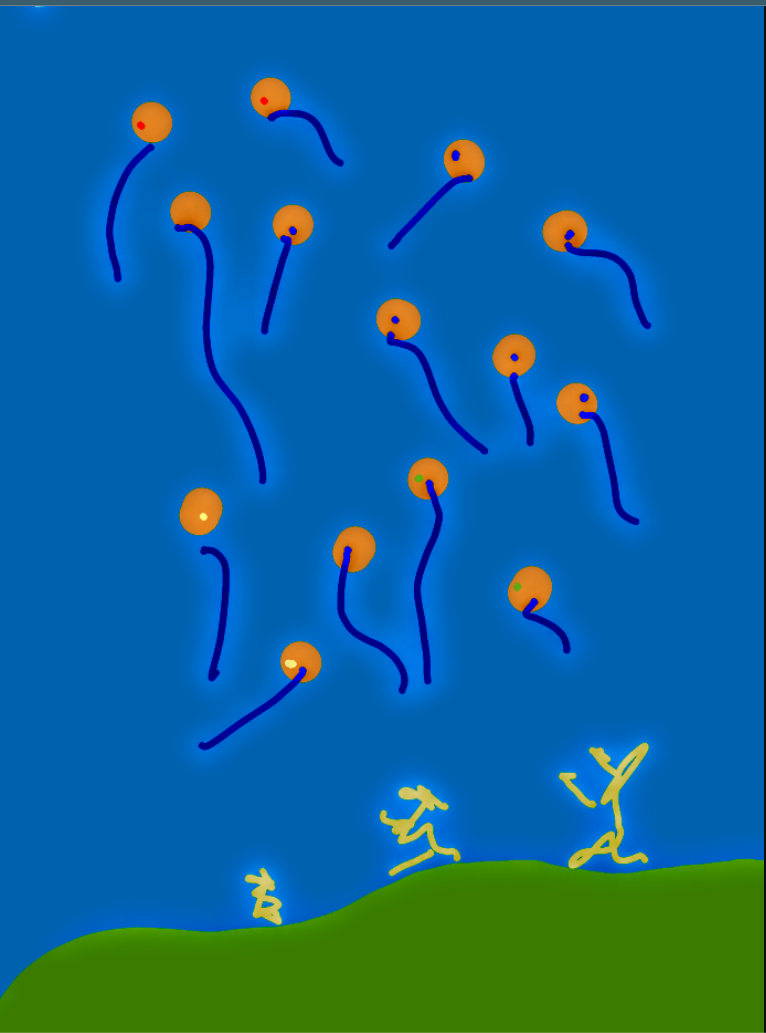

Recently, over at The Arc, a non-profit thrift store not far from us, out on the sidewalk, against the wall, behind some smaller items, I spied a large canvas, 26″ x 60″ x 1 & 1/2″. They wanted $10 for it. A great find. The visions of what I might paint over it started drifting in like a slow moving moon, the light in a park changing by the minute. But when I got the painting home, a canvas print of some sort, the kind used to decorate hotel rooms or small business lobbies, I began to have second thoughts about painting over it. Something about it said no, put me up as is.

So I did, and here it is, for your critical review. Please leave a comment! Is it art? Is it good? Why, why not? …B, care to comment? Ashen? Dan? Bill? Barbara? Lisa? Susan? All you artists and art aficionados out there?

The pic in the bottom right corner shows one of my basement paintings, sitting on the piano, which I took down to hang the Arc find.